Claudia Neugebauer, Claudio Nodari

1. Introduction

The theme “comprehensive language promotion” has three dimensions in the context of the present book:

- The school-based appreciation of multilingualism and the promotion of bilingual or multilingual upbringing of the students. For more about this pedagogical postulate, see chapter 4.

- Furthering the competence in the language of the school and the host country. The respective skills are critically important for the school-based selection, the career prospects and the integration into the host country; they should be purposefully and deliberately promoted in most subject areas.

- For children and adolescents with a migration background: the comprehensive furthering of the competences in the first language, with the goal of a balanced development of bilingual competences in the oral and written form (bi-literacy). Without a targeted promotion, most of all in the written and standard variant of the first language, many of these children would remain illiterate in their first language and lose the contact with their written culture (see the autobiographical accounts of HLT students in chapter 8 B.1 and Agnesa‘s bitter experience in 8 B.2). It is clear that HLT plays a particularly central role for children and adolescents from educationally more disadvantaged families, as the parents would be overwhelmed with the respective tasks.

The following remarks refer to the backgrounds and models for language and textual skills which apply across the board for the first and the second languages. Direct references will of course be provided to HLT and its students wherever possible.

The distinction between school language and everyday language plays a decisive role in comprehensive language promotion in the context of a multilingual environment. The language of the school differs substantially from everyday language, be it in HLT or regular classroom instruction.

On the one hand, a school-specific vocabulary is used (for lecture hall, learning activities, school-related objects, etc.) and specific grammatical forms (passive constructions, subordinate clauses, etc.), which are rarely encountered in everyday language. On the other hand, learning in school demands a pronounced competence to interact and deal with situation-unrelated and textually-shaped language that is deliberately structured and planned.

In what follows, the relevant dimensions of language competence for learning in school are presented. The differences between everyday and school language will be discussed against this background, and the concept of textual skills will then be introduced. The chapter concludes with specific examples that show the ramifications of the advantages derived from comprehensive language promotion in HLT.

2. Dimensions of language skills

The meaning of the term “language competence” comprises abilities and skills on various levels of language processing and voice/language application. Portmann-Tselikas (1998) makes the following distinction:

- a) Language competence in a narrow sense

- b) Pragmatic competence

- c) Verbal reasoning skills

- d) Strategic competence.

A good summary of goals and guiding principles, respectively can be found in chapter 3 of the Zurich framework curriculum for native language and culture, which can be downloaded in 20 languages from the internet (see bibliography).

a) Language competence in a narrow sense

Language competence in a narrower sense includes knowledge of the language system: it requires a certain vocabulary, knowledge of grammar, phonology and prosody (stress, rhythm, etc.) of a language, which makes it possible to understand and to express oneself.

Language competence in a narrower sense therefore consists of certain fundamental linguistic skills which enable people to adequately express themselves in a certain language in the first place.

As vocabulary, grammar, phonetic system and phonology differ in various languages, language competence must be acquired anew, at least in part, for every new language.

The students in HLT for the most part have as much first language competence in the narrower sense, in that they are at least capable of simple daily conversations. However, their level of language proficiency is often significantly lower than the level of same-age students who grow up in the country of origin. An inherent problem with certain languages is the fact that children from educationally disadvantaged, less literal families tend to speak the first language only in a dialectal variety. As a result, communication in class is impaired until a certain level of competence in the commonly-used variety (mostly the standard or written variety) has been attained.

Reflections about different varieties of the first language (standard, dialect, patois, language of older and younger people, slang, code-switching/language-mixing) and comparisons with the second language are valuable and helpful for the linguistic orientation and consciousness (language awareness) of children who grow up multilingually. HLT instructors can and should create appropriate learning opportunities time and again, beginning with the lowest levels in order to encourage students to engage in simple language and dialect comparisons on a lexical and grammatical level.

b) Pragmatic competence

Pragmatic competence refers to the knowledge of culturally conditioned behaviors in a certain linguistic or cultural region. A person with pragmatic competence is able to behave in a suitable way in different social situations of a linguistic community. S/he knows, for example, how to address elders and persons of respect, what questions one may or may not ask of another person, or how, when and whom to greet appropriately.

Pragmatic norms differ from language to language and often even within the same language area.

People who live and grow up in a different cultural or linguistic community must therefore get to know and respect the specific norms of the new community, if they do not want to appear as antagonistic or impolite.

The discussion of culture and language-specific pragmatic norms is a recognized component of language instruction today and also leads to important learning causes and thoughtful reflection in HLT classes. They are all the more attractive and authentic, the more they connect directly with the experiences of students who grow up in and between two languages and cultures.

For instance, the metalinguistic analysis of pragmatic norms can be stimulated by questions such as the following:

- What do you know about informal and formal address in our culture of origin and here, where we live now? Who can address whom informally? Who must address whom formally, etc.?

- Who is greeting whom and how? What rules of greetings do you know? When do we use which forms of greeting and leave-taking – here, and in our culture of origin?

- What occurs to you when you compare the two cultures in terms of the following key words: sound volume, body contact, distance between the speakers?

c) Verbal reasoning competence

Verbal reasoning competence concerns the ability to reproduce more complex issues coherently and intelligibly or to understand appropriate texts. It enables a child to follow a story, to understand a multi-step linguistic sequence, or to formulate it him/herself. Verbal reasoning competence is also often required in many situations in HLT classes, e. g., when the communication with the older students occurs exclusively by way of written texts and instructions, while the teacher is engaged in working with the younger ones.

Verbal reasoning competence is not limited to a single language, and therefore must not be built anew in every idiom.

It is therefore more a question of a competence which is acquired only once and then can be applied in all other learned languages.

Ordinarily, the students should transfer the appropriate prior knowledge from regular classroom instruction; HLT can connect with and expand it from there. Verbal reasoning competence can be easily supported with playful exercises for younger students (place pictures in the correct sequence, tell stories according to the pictures, assemble cut-up picture stories correctly, read charts, connect matching parts). Older students work on their verbal reasoning competence, give short presentations for instance, and write reports in accordance to clear instructions.

d) Strategic competence

Strategic competence comprises the ability to solve problems with oral communication and language learning.

Learners with a high strategic competence know how to ask for clarifications when confronted with communication difficulties, for example, or where and how to obtain information from books and the internet, how to ask for assistance or how to proceed if one has to understand or express something that is linguistically complex. Like verbal reasoning competence, the strategic competence is not tied to a certain language either and can be utilized in various languages.

HLT can promote the strategic competence with well-structured and repeated work assignments. Speech actions that are performed repeatedly in the same way in classroom instruction, such as marking, repeating something after someone, memorizing, finding words in a text, planning a text, looking up something/researching, etc., will become routine over time. Experience shows that the reflection about such procedures (to become aware of the strategies) is possible with younger students and has a positive influence on the development of strategic competence.

Particularly enhanced learning promotion: coordinated approach

Verbal reasoning competence and strategic competence are critical for success in school. These competences are not tied to a specific language and can be furthered in HLT, as well as in the second language or national language classroom. A coordinated approach by HLT as well as regular class instruction would be ideal. If the students in HLT as well as the regular classes practice finding and marking important passages in a text, it would double the effect: they have more practice time and become aware that this approach is useful in any language.

It is well worthwhile if HLT instructors make contact with regular classroom teachers in order to inform themselves about their current strategies and the approaches currently pursued and practiced in regular classes, which could be taken up by HLT.

3. Everyday language – school language, BICS – CALP

The Canadian educational researcher Jim Cummins first introduced around 1980 a distinction betweeen two kinds of linguistic competence: BICS (Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills; a basic capability for everyday speech) and CALP (Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency; cognitive school-related communicative abilities). Everyday language competences (BICS) are largely learned through social contact by all humans. To engage in everyday conversation, read and write short information like SMS, ask for directions, etc., are speech acts which do not require educational promotion. However, if more complex speech acts (CALP) are involved, cognitive school-related communicative competences are required. They correspond largely to the above described verbal reasoning and strategic competences and are supra-linguistic, i. e., students who have acquired them in one language, can rely on them for other languages as well. They are critically important for student success and thus for professional perspectives and social integration as well. This is the main reason why a coordinated approach in this respect between HLT and regular schools is absolutely desirable in the interest of the students.

The interdependence hypothesis

There is a certain relationship or interdependence between the individual languages which a person speaks. With the so-called interdependence hypothesis, Jim Cummins was able to explain why children from educated families and with a good academic foundation are able to learn a second language faster and more efficiently than children from linguistically weak and educationally challenged families. Thanks to the pronounced CALP competences which educated parents transmit through their differentiated language behavior, the telling of stories, the explanation of concepts, etc., a child from such a family can concentrate on the mere linguistic challenges (vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, pragmatics, etc.). Conversely, children from lesser educated families who do not grow up in the school or local language must simultaneously build up not only the second language but also the (CALP) educationally-cognitive competences. This presents them with a twofold linguistic challenge and is one of the reasons for weak school performances.

HLT instructors can make an important contribution to improving the chances if they themselves coordinate with regular classroom instructors as actively as possible the building of CALP and the verbal reasoning and strategic competences.

4. Textual competences

Language didactics differentiates between the following four skills or areas: listening, reading, speaking and writing. Performance within each of these areas, however, depends on cognitive challenges of varying degrees. For instance, it is comparatively much simpler to write an SMS than to compose a detailed report. Similarly, the cognitive demands are significantly lower when students chat about their vacations than when they have to give an oral report in front of an audience about a historical epoch in their home country.

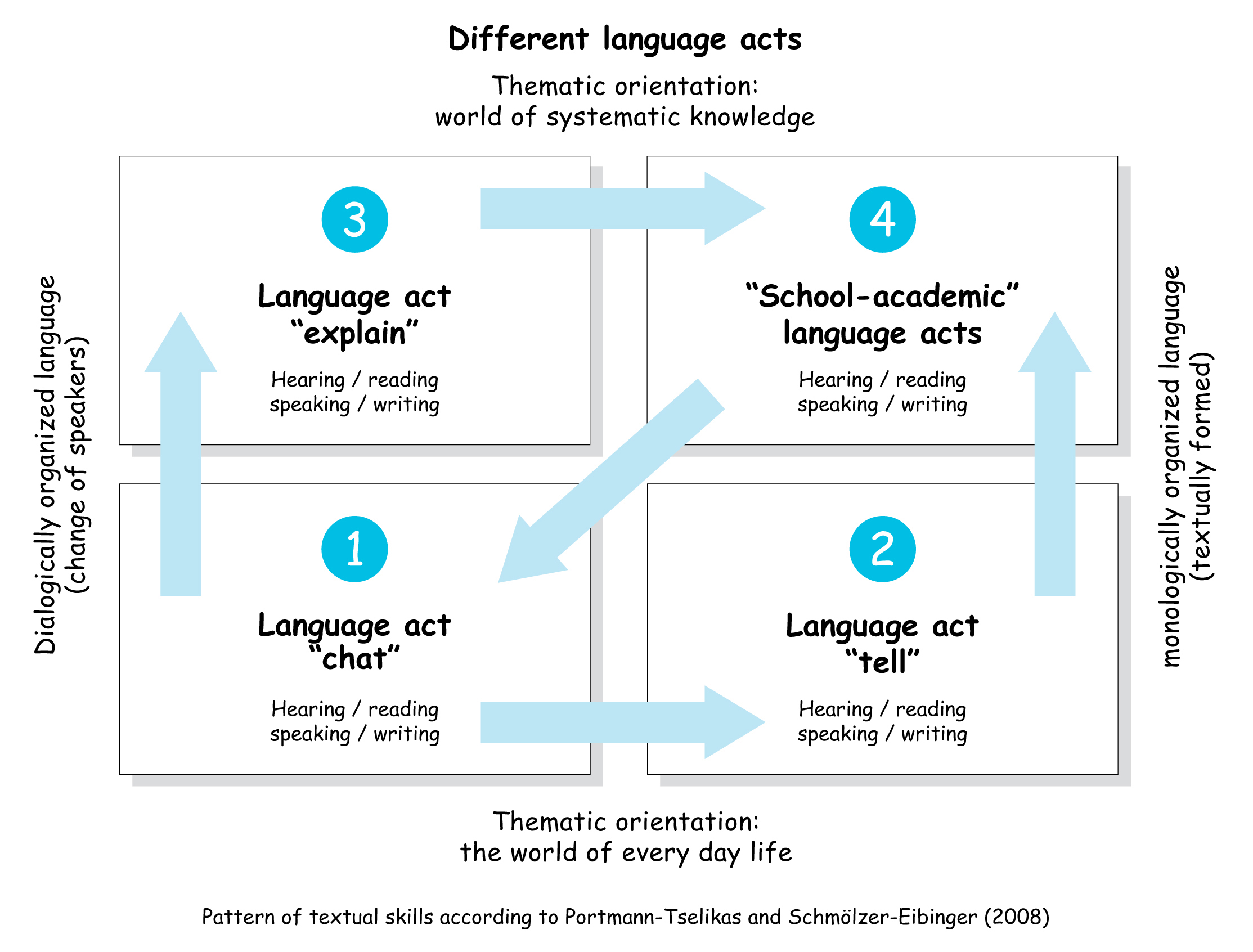

What has been described in the previous chapters in terms of verbal reasoning competence and strategic competence, and school-related cognitive competences (CALP) respectively, is defined as textual competences by Portmann-Tselikas and Schmölzer-Eibinger (2008). With this model, they differ with Cummins’ BICS-CALP model. Their textual competence model differentiates between four areas of linguistic performances.

On the one hand, there are the reference values

- the thematic orientation of everyday life.

- the thematic orientation of systematic knowledge.

On the other hand, the textual competence model distinguishes between

- dialogically organized language products and

- monologically organized, i. e., textually formed, “shaped” language products.

Since the textual competence model is not only relevant in terms of the current discussion on language didactics, but also of interest and importance for HLT and the language promotion that occurs there, we are going to elaborate on it a little further in what follows.

1. Language act “to chat”

Quadrant 1 references dialogically oriented language acts within an everyday context. This includes a large portion of our linguistic-cognitive activities, particularly from the area of leisure time. Although people exchange new information in conversational situations of this kind, little new knowledge (in the sense of new connections and circumstances, etc.) is added and expanded.

The language acts in question are rarely or not at all planned, mostly spontaneous, and often repetitious and redundant.

They can be summarized with the term “chat”, although unambitious written forms belong to this quadrant as well (reading and writing of short messages, SMS, greeting cards, shopping lists, etc.).

The cognitive competences required to function in this quadrant are acquired in social contacts from very early on, and in the individual’s first language. When children enter school, they already know implicitly how dialogical speech takes place. What they need to learn most of all in class and in HLT are additional words, as well as the specific and pragmatic norms of speaking in a group.

2. Language act “to tell”

Quadrant 2 refers to language acts in which the language products are significantly more textually shaped “informed”. These includes all sorts of stories, reports and other narratives. A fairy tale, for example, which is related by an adult person, has a strong textual reliance, i. e., it is told mostly in complete sentences, with a complete narrative arc and a more sophisticated vocabulary. The same is true, of course, for written stories, reports, essays, etc., with a level of sophistication that is significantly higher than chatting. The cognitive competences required of children in order to follow a story, discuss stories and to create narrative texts themselves are developed on the basis of the competences included in quadrant 1. This begins at a very early stage, for instance with bedtime stories.

Children from educated families, where stories already play an important role from the second year on, are capable of following a story through mere linguistic impulses from very early on.

Children who grow up with stories therefore learn early how to produce inner (mental) pictures from linguistic input, and to see a mental picture and talk about this inner film. (This is also referred to as mental representations in this context.) On the other hand, children from language -poor families, where no stories are told, frequently lack precisely these competences when they enter kindergarten. Schools and HLT should and can make at least some limited compensatory efforts in this area in that they include story telling and deliberately manage and engage in discussions about stories and the creation of mental pictures.

3. Language act “explain”

The foundations for the cognitive competences in quadrant 3 are also established early on, namely in the so-called „why“ age. As soon as children begin to ask „why“ questions, they are confronted with complex answers. Parents who respond to „why questions“ by engaging children in intensive conversations, not only teach them important worldly knowledge, but contribute substantially to building cognitive structures, such as cause and effect relationships (if – then), condition/concession (if…) or different “if” scenarios (this would only be so, if…). Speech actions in quadrant 3 are dialogically organized, i. e., the communication partners alternate in the role of the speaker, although not as often as in quadrant 1. These conversations may include longer monological sequences, for instance when an adult person exhaustively explains something to a child, or when a child would like to understand something clearly. The written texts in this quadrant could, for example, also include an interview with an expert, in which a question would each time be followed by a more or less exhaustive answer.

Many children from educationally disadvantaged families lack the experiences with explanatory discussions, and their cognitive competences are therefore only partially developed.

With regard to the competence “explain”, HLT has two important tasks: first, it must offer appropriate assignments; e. g. “explain why something (an action, a cultural or historical fact, etc.) is such and such!”. Second: it must support the students in fulfilling the task in terms of the structure and vocabulary in the first language. This often requires special preparations, as many HLT students have difficulties with the more demanding aspects of their first language.

4. School-academic language acts

Quadrant 4 refers to oral and written language acts which are textually informed (ambitiously shaped) and impart new knowledge content-wise. Children encounter such texts most of all in the context of the school. They must follow short factual explanations (listening comprehension). At the primary school age, they will be asked to give a short presentation about an animal (speaking), to read a factual text (reading comprehension), or to write down the sequence of an experiment (writing). These language acts require cognitive competences that must be built and expanded in school and which are based on a well-developed foundation in quadrants 2 and 3.

For student success, the cognitive competences in this area are fundamental, see also the references to CALP.

HLT can of course rely on competences and techniques in terms of these quadrants which students carry over from regular classroom instruction. However, it can and must create learning events (and offer the corresponding support) whereby these competences are also transferred to topics in HLT and the language of origin.

Complex language acts through educational support

Language development originates in quadrant 1. Only after a small child has built -up fundamental communication abilities can the competences in quadrants 2 and 3 be developed. If children were unable to build at home the cognitive competences in quadrants 2 and 3, it is the task of kindergarten, school and HLT, to purposely further them in these areas – for instance, through repeated story telling and re-telling of simple stories or through explaining and demonstrating of procedures and facts in an age-appropriate simple manner.

The competences in quadrant 4 can only develop if the children have already acquired the fundamental competences in quadrants 2 and 3. There is no direct path from quadrant 1 to quadrant 4. However, there are repercussions of cognitive competences from quadrant 4 to quadrant 1: people who have learned to write a text or relate an event clearly and understandably, etc., generally also speak in another, more differentiated manner in everyday situations than those who show no or only weak competences in quadrant 4.

The special task of HLT in these processes is to further the children so that they accomplish these steps and developments in the language of origin as well.

Many students are indeed significantly stronger in the school language of the host country – which is not surprising, as they are furthered in the language of the school for 30 lessons per week, but only two lessons of first language study in HLT! It is therefore all the more important that these two lessons are used in the most efficient and language supportive way.

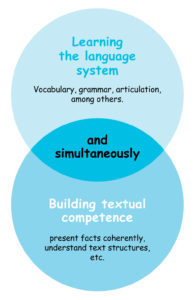

A double challenge: learning the language systems and simultaneously build text competences

For language support in a multilingual environment in general, as well as for HLT, it is especially important to note that language instruction must simultaneously focus on two different linguistic dimensions:

On the one hand, the learning of the language system must be supported. For HLT, this refers primarily to the system of the standard or written variant of the language of origin.

On the other hand, different facets of the text competence (CALP, verbal reasoning competence and strategic competence, see above) must be simultaneously developed and expanded, as they are critical for school and educational success, respectively. In this context, HLT can and must relate to that which students carry over from regular classroom instruction.

The more the HLT instructors and the regular curriculum teachers cooperate and, for example, practice the same reading and writing strategies in the first and second languages, the more sustained and robust the learning effect turns out to be.

A one-sided focus on learning the language system contributes little to a child’s successful learning in school.

5. Consequences for a comprehensive language promotion

Practical experiences show that dialogical language acts play a dominating role in most teaching activities. In the graphic of the four quadrants of textual competence (see above) these language acts are assigned to quadrants 1 and 2. The instructor, for example, exchanges views with the students about vacations (quadrant 1) or s/he speaks with them about agriculture in the country of origin (quadrant 3).

A comprehensive language promotion is premised on the idea that in all subjects where language plays an important role, even monologue-based language acts – language acts of the quadrants 2 and 4 – should be purposefully promoted. The following didactical example shows how this should and can happen in HLT and with respect to the language of origin.

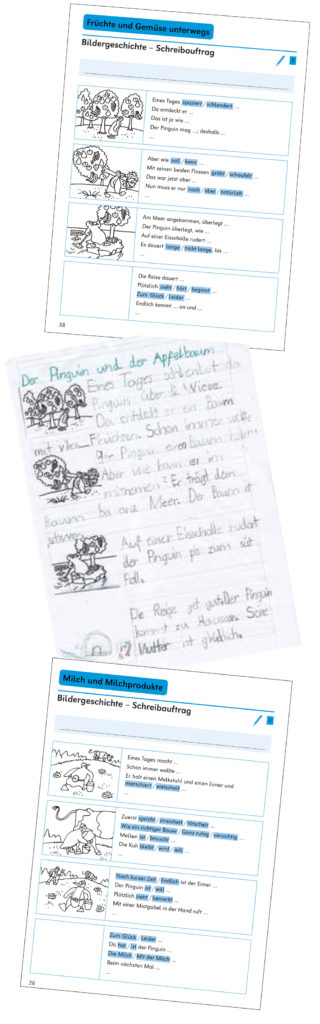

a) Enable complex language acts through supporting tasks

Supporting tasks for speech or writing are instructions or directions which offer students language material and assistance for structuring and creating of a text. An example are the various beginnings of a sentence and linguistic building blocks, which are depicted in chapter 7 B.4. They help the HLT Spanish students of St. Augustin‘s School in London to put more variety in their text creations.

Students can be accompanied with supporting tasks which enable them to use words, formulations and constructions in speaking and writing which they could not yet have productively applied without help.

In language didactics, this is called scaffolding (derived from scaffold = support platform). The tasks form a scaffold which by and by will no longer be needed – once routines have been developed. When students show high performance with scaffolding support, this often leads to an increased and performance- enhancing motivation. Moreover, regular work with supporting tasks leads to a gradual build-up of a repertoire of linguistic means and strategies for the development of routines which are applied more and more independently.

The following examples show how a linguistically challenged eight year old child creates a text for a picture story. The child receives a template (see right), from which the structure and a few given sentence blocks can be derived. In the third sentence of her own text, she even uses a sentence block which she learned in a previously written picture story (“he always wanted to…”); see next page. This shows that text blocks can also be stored and retrieved for later texts.

The “scaffold” is internalized over time for a certain kind of texts (e. g. a picture story). The teacher can now begin with a new type of text (e. g. simple presentations) and initially provide helpful scaffolds or parts of speech, respectively.

Needless to say, similar templates can also be created without problems for HLT in the language of origin. Areas of application: scaffold for picture stories/ essay about an experience/ for factual texts/ for small presentations (structure; formulas for beginning and end, etc.); collection of sentence beginnings and other language elements as in chapter 7 B.4.

An abundance of pertinent ideas can be found in part III of the workbook “Writing in the first language” of the series “Materials for HLT”.

b) Building a vocabulary base that enables complex language acts

Adults and children learn constantly new words – even without input from school. For successful school learning, this uncontrolled acquisition of words must be complemented with targeted vocabulary work. This is twice as important for the first language or language of origin, where many HLT students are weaker than in the language of the host country, particularly those who do not attend HLT! A special danger here is the so-called disintegration of the vocabularies. This means that the students know the words for domestic and familiar things mostly in the language of origin (although only in dialectal form), whereas for all school-related items (ruler, gym bag, school yard, measure, weighing) they only know the words in the school language of the host country.

An important task for HLT is to prevent this vocabulary disintegration, through targeted, deliberate work on school-related vocabulary in the language of origin.

This can and should always occur by involving the language of the immigration country, as illustrated in the planning example by Etleva Mançe in chapter 8 B.3. (see also the teacher’s statement in chapter 8 B.4: “It has been my experience that the children learn their mother tongue much better with parallel instruction in German and Romani.”)

In order to prepare students for complex language acts, they must be systematically accompanied in a functional vocabulary development that extends beyond everyday language needs. In pursuing this goal in practice, it has been proven successful when teachers write a short text in preparation of a topic which is formulated in the manner expected of the students at the end of the respective learning unit. For younger students the teacher can imagine a text narrated by a child, with older learners a text in written form.

Such a fictitious student text illustrates which words and phrases are important for the work on the topic. The relevant words are marked in the fictitious student text. This provides the basis for the creation of a manageable, age-appropriate list of words which should become part of the productive vocabulary (see below). It goes without saying that two or three word lists can be created for different levels, based on this fictitious student text.

The following example from a continuing education event shows the task given to instructors, and the suggestion by a teacher of eleven to twelve year old students.

- Task

Write a fictitious student text about a current topic in your class. Formulate the text according to the following key question:

What should the students be able to say and write at the end of the instructional unit, which important words should they know and be able to use? - (Suggestion of a teacher)

Topic: stone age – fire

People learned to control fire. They were able to ignite a fire themselves and to use the fire.

The fire offered protection from nocturnal animals and insects and provided light.

Fire enabled the survival in colder regions. Meat could be roasted in the fire. As a result, the meat became more easily digestible.

Furthermore, birch tar – a strong adhesive could be made from birch bark with fire.

c) Productive/active and receptive/passive vocabulary

The differentiation between productive and receptive vocabulary work is important for all vocabulary learning. The productive vocabulary references frequently-used important words and phrases which the students themselves can actively use (in our example: to control, enabled, digestible; furthermore the constructions with the modal verb “could”, etc.). For that, they need application possibilities, e. g. the request to deliberately apply these words 2–3 times in a spoken or written text.

The receptive vocabulary includes more infrequently-used words and phrases which the students should passively understand, but not (yet) necessarily acquire for their own application (in our example: kindle, birch tar, etc.).

Concerning the words which “only” need to be understood, the following distinction may be useful:

- 1. Words, phrases, constructions, constructions of lower utility value: a short – generally oral – explanation is sufficient.

- 2. Words, or formulations which may be needed repeatedly in later work on this topic – e. g. in reading texts or lectures by the instructor: in which case it is useful to not just clarify the meaning, but also to retain its significance.

In working with specialized texts in particular, many words or formulations are frequently discussed orally. Learners for whom most of these explanations are new have barely a chance to retain all the information. Thus, explanations can be recorded on a poster, in a word book, with marginal notes, or on sticky notes, so that they are available for later applications.

d) Important for more complex speech acts: means for linking/connection

Students need a special group of words, such as “while”, “but”, “soon” or “suddenly” for instance, such that more complex formulations and references can extend beyond the sentence boundaries. In class, these words are rarely explicitly examined. They are equally rarely included in word lists which teachers create for their classes. (see the posters in chapter 7 B.4!)

The function of these words is to connect thoughts in sentences or texts. For this reason, they are called “function words” or “linkage means”. So that learners understand the meaning of connectors, they have to see them embedded in meaningful relationships (contexts). When the text of a student is read aloud in class, the teacher can pick out a sentence with a connector and ask about its function. Even younger students show already an interest in meta-language questions of this kind. This may be an opportunity to discuss why in a certain position the word “or” instead of “and” must be used. With older students, the different meanings of sentences like “we won’t go out, because it rains” and “we won’t go out, when it rains” could be discussed. In particular discussions concerning the impact of words and phrases, such as “suddenly”, “after a while”, “I was eagerly awaiting…” can give students suggestions/ideas for their own writing.

It is clear that relevant reflections (as well as the comparison with the classroom language of the immigration country) can contribute much to raise the sensibility towards the language of origin and to raise the competence in the mother tongues as well.

Bibliography

(see also the workbooks of the series “Materials for the native language education classroom / didactic applications”!)

Bildungsdirektion Kanton Zürich (2011): Rahmenlehr- plan für Heimatliche Sprachen und Kultur (HSK). Link: http://www.vsa.zh.ch/hsk

Cummins, Jim (2000): Language, Power and Peda- gogy. Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Clivedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Cummins, Jim (2001): Bilingual Children‘s Mother Tongue: Why Is It Important for Education? Link: http://www15.gencat.net/pres_casa_llengues/ uploads/articles/Bilingual%20Childrens %20Mother%20Tongue.pdf

(Deutsch: Die Bedeutung der Muttersprache mehrsprachiger Kinder für die Schule; Link: http:// www.laga-nrw.on.spirito.de/data/cummins_ bedeutung__der_muttersprache.pdf).

Krompàk, Edina (2014): Spracherwerb und Erst- sprachenförderung bei mehrsprachigen Kindern mit Migrationshintergrund. In: vpod Bildungspoli- tik, Sonderheft Nr. 188/189 “Die Zukunft des Erstsprachunterrichts”, p. 20 f.

Neugebauer, Claudia; Claudio Nodari (2013): Förderung der Schulsprache in allen Fächern. Praxisvorschläge für Schulen in einem mehrspra- chigen Umfeld. Kindergarten bis Sekundarstufe I. Bern: Schulverlag plus.

Portmann-Tselikas, Paul R. (1998). Sprachförderung im Unterricht. Zürich: Orell Füssli Verlag.

Portmann-Tselikas, Paul R.; Sabine Schmölzer-Eibinger (2008): Textkompetenz. In: Fremdsprache Deutsch, vol. 39, p. 5–16.