Dora Luginbühl, Xavier Monn

1. Introduction

Ideological and cultural values, notions of instructional quality and aspects of modern school developments manifest themselves in methodological and pedagogical activities in the classroom. Support orientation, autonomy and individual responsibility as well as relevance to everyday life or age-appropriateness (see chapter 5) demand an expanded understanding of teaching and learning.

Moreover, the heterogeneous make-up of the classes (based on cultural, social and cognitive differences) demands that teachers and schools develop differentiated teaching methods. These are more strongly aligned with the different requirements and possibilities for cognitive development of the students than before.

The aim of the chosen measures of internal differentiation and adaptive instruction is to provide all students with the greatest chances for optimal learning and custom-fit learning programs. The characteristics of learning-effective teaching are, at the same time, neither ignoring the existing differences nor a “radical” individualization, which demands a separate program for every student.

Learning-efficient instruction rather distinguishes itself by a deliberate, goal-oriented and balanced use of different teaching and learning methods, and very much pertains to HLT as well. It balances learning objectives, course content, learning time, as well as the learning locations, if applicable, with students‘ different requirements, and includes different illustrative and working materials. The teachers further students‘ learning and comprehension processes with appropriate tasks. They accompany the students with follow-up and advice in class, in groups, or individually in preparation for the next learning steps. Thus, differentiating is possible in guided as well as in open instructional sequences.

The following aspects are essential for an appropriate selection of teaching and learning methods:

- Learning effectiveness for students,

- Adaptive and customized choice of methods,

- Methodological competence of the teacher.

These will be elaborated in the ensuing sub-chapters along the themes of teaching and learning in heterogeneous classes, expanded teaching and learning methods and learning tasks, particularly with reference to HLT. It is imperative to include the sometimes very different contextual conditions for HLT in methodological considerations. The mostly separate classes, which are already partially marginalized in terms of room availability as well as time table, cannot build on the same methodological foundations as the regular classes in public schools.

The present overview follows largely the brochure “Learning and lesson comprehension” (Thurgau Department of Education, 2013), created by co-author Xavier Monn for the Education Department of the Canton of Thurgau, with portions taken directly from the brochure for this text.

2. Teaching and learning in heterogeneous classes

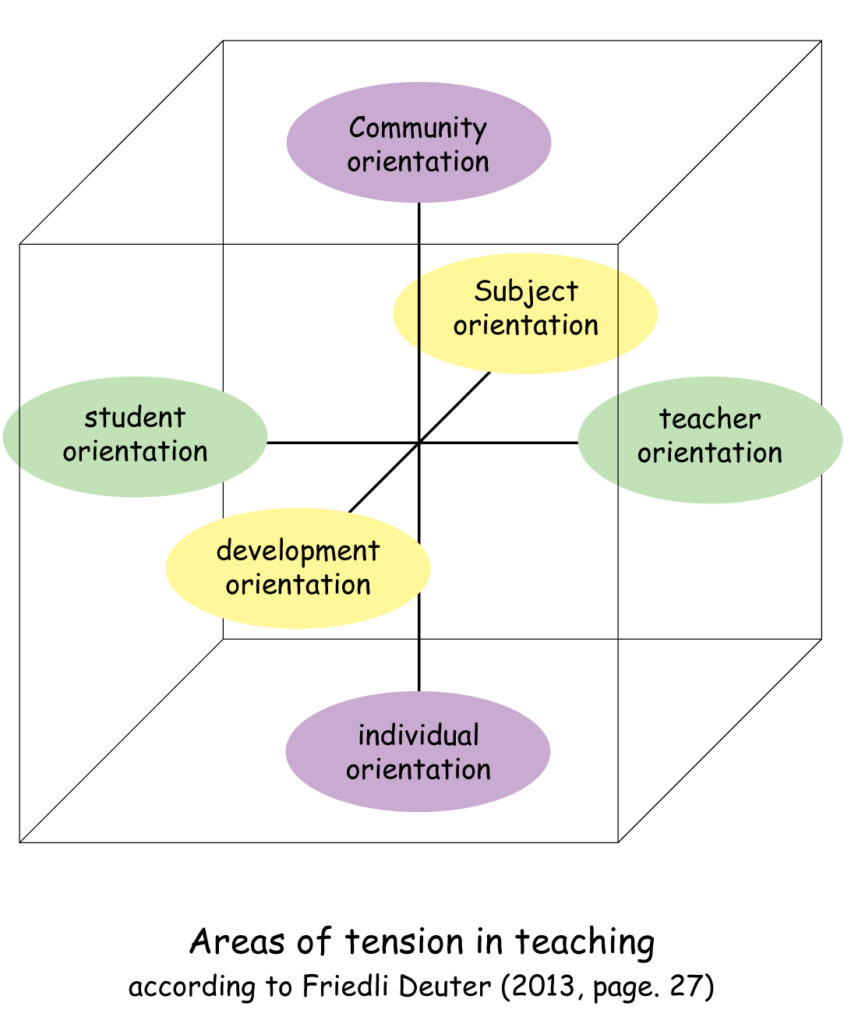

Classroom instruction that is aligned with the heterogeneous requirements of the students must develop with partially contradicting requirements and goals. This creates various areas of tension, as shown in the cube model in figure 1 (by Friedli Deuter 2013, page 27; based on an unpublished script of Eckhart and Berger). Regarding the choice of learning content, it involves mediation between the subject orientation (e. g. learning objectives according to the curriculum) and the orientation along the development level of the children and adolescents. Additionally, the dimension of differentiation requires a constant balancing between the needs of the individual and the need for shared learning experiences (community orientation). Another field of tension opens up in the dimension of instruction and classroom management. Where is student-centeredness conducive to learning and where is a rather direct teaching approach more appropriate, with the teacher directing the learning process?

An instructional approach with heterogeneous learning groups is therefore not an either-or- principle, but rather a both-as-well- as principle. It requires a constant, situative and goal-oriented balancing of opposites along the referenced baselines.

This represents a challenge for teachers: “moving about within such instructional areas of tension can create insecurity. However, it also opens up instructional latitude, and can encourage learning and experimenting with different approaches that complement each other. This must not lead to arbitrariness […], but demands a reflexive practice in which classroom instruction continues to be developed so as to better meet the manifold learning and performance requirements of the class” (Eckhart 2008, page 107).

In this context, Meyer (2011) refers to instructors‘ “balancing tasks” and suggests the following concerning the quality criterion “variety of methods”:

- Analyze and incrementally enlarge the personal repertoire of methods

- Balance class work, on projects and independent work

- Balance work in plenary, in groups and independent assignment

- Systematic work on students‘ repertoire of methods (no isolated method training, but integrated into the work on content-related assignments)

- Incorporate forms of cooperative learning into classroom instruction

- Plan competence assessments, look for or develop appropriate instruments

In addition to the generally applicable suggestions, HLT instructors will face other, HLT -specific balancing tasks:

- Balancing between the teaching/learning expectations of the host country and the ones of the teachers‘ own culture of origin.

- Mediation of first languages, which are often minority languages with ‹low status› in the immigration society.

- Short instructional periods, which are not part of mandatory classroom education.

Aside from these demanding balancing challenges, HLT is based on voluntary school attendance, which is sustained with significant family support (see also chapter 2).

The following questions are suggested as an orientation aid for the specific discussion of the dimensions of the cube model. They may also serve as a basis for reflection and discussion of one’s own teaching:

- Are there differentiating forms of work (planned work, workshop, work stations, etc.)?

- What significance does the learning content have for the individual students (relevance to everyday life, see chapter 5 as well as 6 B, example 1)?

- Are group formations deliberately shaped (gender, achievement, age, interests)?

- In which situations is cooperation initiated, practised and lived by?

- How are conflicts resolved? Intercultural conflict training as part of HLT

- Are there team-building activities and forms (rituals, projects, class council)?

- …

- Can there be differentiation between core subject matter and additional content?

- Are learning contents and learning objectives differentiated to the extent that they are appropriate for different levels of competence and and difficulty? (see 6 B, example 2)

- Are different tools available for the visualization and demonstration of the learning process?

- Are there instruments to assess the stage of learning and development of individual students in their first language or language of the family?

- Are learning groups formed on the basis of different levels of competence?

- …

- Are the teaching and learning methods varied?

- How are the students guided to become self-directed learners?

- How is the learning environment structured?

- What kind of educational assistance is there?

- How are the learning processes followed-up, and documented (e. g. portfolios)?

- How are the sequences of tasks planned?

- How are the weaker students guided and supported?

- Is there a tutor system (learning partners, tandems)?

- What kinds of rules, agreements and boundaries ensure a good working atmosphere?

- …

The instructor’s role in the teaching and learning process changes according to his/her movements within the outlined dimensions of the cube model. The choice of the teaching model depends again on the instructors‘ understanding of their teaching role.

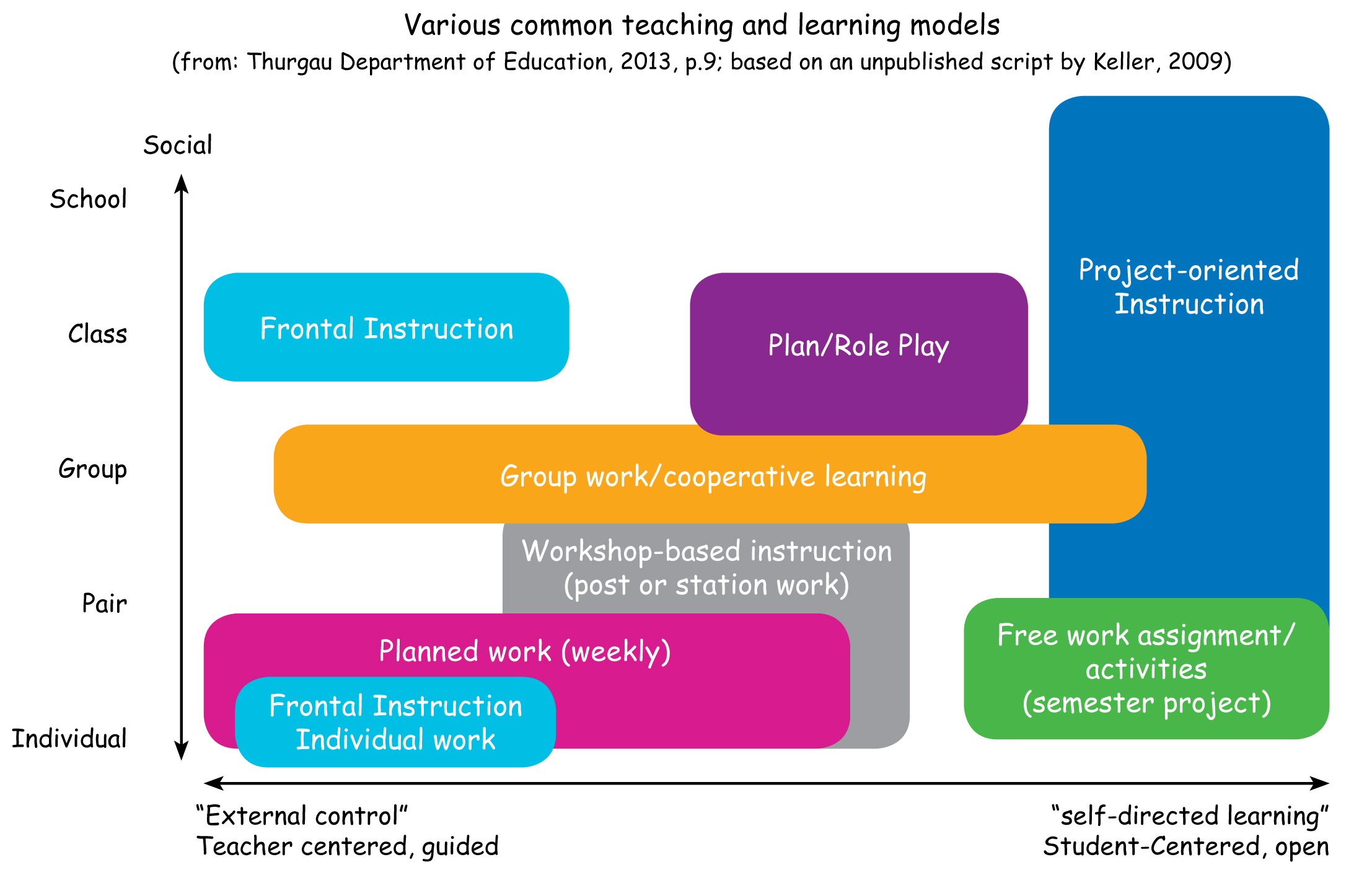

3. Expanded forms of teaching and learning

As shown above, teaching in the traditional sense of presenting, explaining, assigning tasks and queries is still important, but self-directed learning is increasingly gaining ground. Figure 2 below illustrates some of the frequently used teaching methods in practice according to their social setting and general classroom management. The various methodological approaches that can be found in today‘s public schools are located along the vertical axis “social setting” (ranging from individual tasks all the way to whole school assignments), whereas the “external control” (guided, teacher-centered instructional forms) and “self-directed” (open, student-centered classroom instructional forms) are located between the posts on the horizontal axis.

Caution should be exercised with the horizontal axis “external control – self-directed”, as terms like “teacher- centered/guided” and “student- centered/open” are very general paraphrases of instructional forms that refer to guidance by the instructor. As such, they can easily lead to polarization. Open learning situations in themselves are neither superior nor inferior to guided instructional sequences. The extent of openness or guidance, respectively, is not critical for the instructional quality. Guided instructional sequences may very well include open and cognitively stimulating tasks. In open learning situations, where students themselves decide on the sequence, duration and social setting, for instance, the offered options may in turn be highly restricted, with a prescribed work approach and problems that can only be solved with one correct solution. This is important for HLT. Instructors who are primarily accustomed to an externally, controlled frontal teaching style from their own training, may very well want to expand their methodological repertoire very cautiously in a small, step-by-step approach. The goal of learning-effectiveness should always be the primary aim of teaching preparation and reflection. In doing so, it is always important to consider the following: the more open the instructional model, the more it requires a clear structuring. The learning system in the open learning model is not a small-step, linear process. Rather, learning takes place in an experiential environment where various pathways are possible. Certain coordinates provide orientation and help in pursuing an important learning objective.

4. Different methods of teaching and learning at a glance

None of the various teaching and learning methods can deliver everything. Each has advantages and disadvantages and is especially well suited for specific strategic goals and learning contents. The following partial summary will offer an overview, with the main focus on the so-called expanded teaching and learning forms. A variety of methodological variations of these basic forms are presented in a clear and concise manner in the book “Methodenprofi” (in English “Professional of methods”) (see Assmann, 2013).

|

Frontal teaching Is a mostly thematically oriented and orally mediated teaching style. The instructor directs and controls the working students in a class. This also includes phases of individual work. |

|

| Significant key aspects |

|

| Examples for implementation in the classroom |

provide overview mediation of basic factual information, which is fundamental for further learning progress |

| Important for HLT |

It is good to repeatedly intersperse short sequences (5–15’) of individual work (or with a partner), that comprise tasks that can be solved in different ways according to the students‘ level of competence. |

|

Workshop teaching (Post or station work) signifies the presence of work posts “stations” in the classroom or in different locations, where the students autonomously perform learning and work assignments more or less of their own choosing. The learning and work assignments are individually selected in their succession and according to the students‘ interests. The corresponding documents and materials were previously prepared and laid out by the teacher. |

|

| Significant key aspects |

|

| Examples for implementation in the classroom |

|

| Important for HLT |

|

|

Planned work (weekly or daily plan) In planned classroom instruction, learners receive written assignments for various subjects in form of a plan. The assignments must be completed within a certain time frame (e. g. half-day, day or week) and the lessons available. Planned work over just a few lessons would be feasible. |

|

| Significant key aspects |

|

| Examples for implementation in the classroom |

|

| Important for HLT |

Planned work in HLT is only possible in reduced timeframes, but can be useful for deeper analysis of an individual theme. Pursuant to the introduction, ‹short plans› could be devised for an instructional unit, tailored to the students‘ learning needs, which contain numerous assignments and offer the children a choice of tasks, which they can perform autonomously. This allows the teacher to work and converse with the children individually and during the lessons |

|

Group work / cooperative learning Refers to learning arrangements, such as partner and group work, where students collaborate to find a common solution to a problem, or to develop a common, shared understanding of a situation. |

|

| Significant key aspects |

|

| Examples for implementation in the classroom |

|

| Important for HLT |

All forms of pair and group work down to the group puzzle (see 6 B, example 1) or other forms of cooperative learning can be easily implemented in HLT instruction. |

|

In project-oriented instruction a group works on a common project (assignment, end product). The group plans the approach and works on an action-oriented basis toward the goal. Individual project assignments are also possible. |

|

| Significant key aspects |

|

| Examples for implementation in the classroom |

|

| Important for HLT |

More extensive projects, which can take an entire week in regular school classes, are less easily implemented in an HLT context. Example 2 of 6 B is fundamentally designed for a project-oriented classroom. Smaller-scale projects are, however, perfectly implementable. |

|

Free work assignments/ free activity Learners go for a specific period (ranging from a half hour per week to a long-term semester project) and pursue their own interests, issues and discoveries, thereby gaining new experiences and deeper knowledge. |

|

| Significant key aspects |

|

| Examples for implementation in the classroom |

|

| Important for HLT |

This form of instruction has limited applications for HLT, owing to its inherent time constraints. However, it can be easily combined with highly popular workshops and projects, which should also be implemented once or twice a year. This could occur in terms of a self-selected activity (e. g. with a theme “from the life of our grandparents”), or in form of a “learning buffet”, whereby the instructor provides a selection of learning opportunities with learning games, books, computer, and printed products as an open self-service learning option. |

|

Role play In this type of activity, learners assume roles in assigned or self-selected situations. |

|

| Significant key aspects |

|

| Examples for implementation in the classroom |

|

| Important for HLT |

Highly appropriate for HLT in all classes. Eventually, a differentiated level and practical assistance can and must be achieved through role instructions. The roles can also be formulated in more detail by the students. |

|

Situation games Reality is re-enacted in these kinds of games by means of determined situations and roles. |

|

| Significant key aspects |

|

| Examples for implementation in the classroom |

|

| Important for HLT |

|

Students can be motivated with a meaningful variation of methodological approaches. Aside from the new forms of learning, factors like today’s new media, new possibilities for knowledge acquisition and learner-appropriate assignments, can motivate students as well (see 6 B, example 2, Internet research).

However, it can easily occur that in spite of good methodological work and variation, truly profound and deep, long-lasting learning is not achieved. Effective learning requires, most of all, creating assignments that motivate and challenge the students.

5. Qualitatively superior learning tasks

The decisive factor is ultimately not the activity, which is visible at first glance, but the mostly less apparent assignment quality and the individual stimulation and activation of the students. This insight is supported by newer research findings of John Hattie (2009). In an elaborate analysis of international effectiveness studies, he was able to demonstrate that – besides the learner factors, which explain half of the performance differences – the greater importance for successful learning (30%) is attached to the instructors and the quality of classroom instruction. Visible structures, such as methodological arrangements are less important than frequently assumed. The stimulating value of assignments which are embedded with fitting precision into the methodological structure is a far more crucial factor (see also chapter 3).

Reusser (2009) distinguishes between surface structure and a deep structure of classroom instruction. Surface structure implies the visible characteristics, e. g., the observable, methodological act of teaching, and the chosen forms of teaching and learning. The deep structure, on the other hand, aims at understanding and sustained learning, which relates to methodical behavior, although it is not in every case immediately observable. The relationship between surface structure and deep structure has not yet been fully clarified. It is safe to say, however, that an expansion of learning forms is helpful for independent and sustained learning processes. It is therefore important to pay particular attention to formulating and creating good learning tasks for any variety of classroom instruction.

Good learning assignments have a central importance in this context. In an ideal case, they fulfill the following criteria (Reusser, 2013):

- They identify and analyze the essential nature of a subject area and facilitate the building of subject-specific knowledge.

- They are embedded in meaningful contexts, have a high relevance in terms of everyday life and stimulate curiosity (see chapter 5).

- They enable and promote the autonomous construction and application of knowledge.

- They motivate students to connect and engage with a learning content and to understand it on a deeper level.

- They allow for practicing with problem-solving and learning strategies.

- They can be solved on various levels and are therefore appropriate for weaker and strong students.

- They allow manifold approaches, ways of thinking and learning strategies.

- They create the preconditions for achieving learning success through effective studying.

6. Conclusion

Many children and adolescents who come to HLT have acquired experiences with enhanced forms of learning in the regular classrooms. Therefore, it is certainly advisable that HLT instructors expand their methodological scope of action as well. This helps to bring HLT and regular classroom instruction closer together and to bridge the gap between the two school types.

It must never be forgotten, however, that the method or form of learning alone does not produce effective learning. Task assignments in most learning forms can be formulated in a way that they stimulate individualized and deeper learning processes. Besides the plethora of methods, it is of paramount importance to pay attention to the respective goal and content-specific approach of the methodological processes and the quality of the learning assignments. The two teaching examples in chapter 6 B substantiate this and illustrate a potential approach with expanded teaching and learning forms in HLT.

Bibliography

Amt für Volksschule Thurgau (eds.) (2013): Lern- und Unterrichtsverständnis. Entwicklungen im Überblick. Frauenfeld. (Download unter: www. av.tg.ch gThemen/Dokumente g Lern- und Unterrichtsverständnis).

Assmann, Konstanze (2013): Methodenprofi. Kooperatives Lernen. Oberursel: Finken.

Eckhart, Michael (2008): Zwischen Programmatik und Bewährung – Überlegungen zur Wirksamkeit des offenen Unterrichts. In: Kurt Aregger; Eva Maria Waibel (eds.): Entwicklung der Person durch Offenen Unterricht. Augsburg: Brigg, p. 77–110.

Friedli Deuter, Beatrice (2013): Lernräume. Kinder lernen und lehren in heterogenen Gruppen. Bern: Haupt.

Hattie, John A.C. (2009): Visible Learning. A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-analyses to Achievment. Oxon:

Keller, Martin (2009): Heutige Lehr- und Lernformen – oder: Vom Lehren zum Lernen. Zürich: Pädago-

gische Hochschule Zürich. Unveröffentlicht.

Meyer, Hilbert (2011): Was ist guter Unterricht? Berlin: Cornelsen.

Reusser, Kurt (2009): Unterricht. In: Sabine Andresen, (eds.): Handwörterbuch Erziehungswissenschaft. Weinheim: Beltz, p. 881–896.

Reusser, Kurt (2013): Aufgaben – das Substrat der Lerngelegenheiten im Unterricht. Profil 3/2013. Bern: Schulverlag, p. 4–6.