Christoph Schmid

1. Introduction

To judge, appraise, examine, measure, test, rate, evaluate, assess, and issue grades and certificates are everyday school activities which have great influence on the learners. They express appreciation, stimulate competition, give pleasure and instill fear, motivate and de-motivate, support self-assurance and destroy self-confidence. Assessment in school pertains to instruction, assignments, performance, learning progress and, most of all, the learners themselves. In class, the instructors evaluate the students – and vice versa, although with different means and consequences. The plethora of assessment activities in school are connected with different value orientations, unfulfillable requirements, contradictions, ideologies, uncertainties and much work.

In order to elucidate fundamental assumptions, the ensuing discussion first deals with recognized postulates and constructs. They are followed by selected components of a pedagogical evaluation perspective for the school.

2. Assessment as a culture and art

To assess knowledge and skills is an art, just like teaching, and much more complex than commonly assumed. There are numerous blinding intuitive practice examples that mask the manifold assessment problems. This begins already with the problematic assertions of follow-up and assessment of learning processes. Learning is a highly complex construct that comprises much heterogeneousness. Mental processes equally elude direct perception, measuring, support as well as monitoring. What is partially apparent to the senses are learning activities and the participating emotions. We use indicators that refer to the process of learning and learned skills. The huge number of potential indicators will have to be simplified and limited in scope.

In the assessment process, the perception has to be sharpened and reduced at the same time – a great dilemma. What must our limited attention always be focused on? And how should we evaluate that which eludes the perception?

The segmented view, with which one has to make do in practice, is much more consequential in terms of fairness and accuracy than the often thematicized perception errors or the trends to perception distortions, like the halo effect, for example, which in the assessment of a characteristic can unnoticeably transfer to other characteristics, or the sequential effect, that leads to previous assessments‘ involuntary influence on the evaluation of ensuing performances.

Assessment activities in daily school operations are part of the social interaction with children and adolescents. They comprise part of the school culture and expressed norms, which are determined by the citizens in a democracy (e. g., see Department of Education of the Canton of Zürich, 2013). Guidelines can be scientifically analyzed, but science cannot be burdened with the stipulation of the actions. Prescriptive statements may not be confused with scientific ones. The determination of what is considered good, is to be negotiated in public discourse.

3. The stress field of promoting and selecting

Teachers have a dual responsibility, relative to the children and adolescents, as well as to society. This is frequently referred to as the contradiction between fostering and selecting. Teachers certify performances with a grade in the grade reports and thereby assist with the selection in the service of society. Performance evaluations, grading decisions and recommendations for an educational career influence the chances for professional opportunities, as those assessments can also be used as basis for a career prognosis. Although they are formative assessments and primarily designed to optimize learning activities and learning conditions for the individual learner, they may have an undue effect on the selection function. In the preliminary stages of important educational transfers, this selection is not infrequently considered as the “sword of Damocles”.

4. Assessment functions

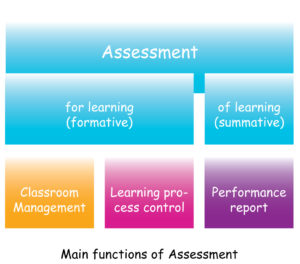

Assessments are supposed to motivate, instill discipline and much more. A dozen different functions and purposes can easily be distinguished (Schmid, 2011, page 239). Depending on the function, a different setting applies, with varying specific approaches or forms. The following overview will focus on two or three main functions.

Whether the assessment serves to improve learning (assessment for learning) or whether it serves to assess someone’s knowledge and skills (assessment of learning) is fundamental. If assessments are conducted, the participants should be informed about their purpose, whether the aim is to improve instruction and learning activities, or to assess and certify their individual personal performances (competences).

In principle, the following is recommended: more promotion-oriented, formative assessments, “assessment for learning” and less “assessment of learning”. The attainment of desired competences must be central to this effort. The summative “assessment of learning”, can serve to motivate and stimulate competition, yet have negative effects on the learning behavior, social interaction and personality development as well.

The following three functions can be described in a somewhat different manner:

- Formative assessment:

Aims to align the teaching and learning activities optimally with the previous knowledge, the learning strategies, goals, needs and interests of the learners.

- Summative assessment:

Gathers and documents information about the level of knowledge of the learner at the end of a learning sequence or a learning period.

- Prognostic assessment:

Provides information for the allocation to certain school types and makes predictions for the school career

(according to Allal, 2010, page 348).

A typical example of a summative assessment is the final grade, which the HLT instructors enter into an official attestation or grade report. This form of evaluation strongly affects the school climate in terms of competition and rivalry in many places. Premature, negative assessments can have dire consequences and teachers in the lower levels should exercise the greatest restraint. Prognostic assessments in the school are possible only to a limited extent and are inevitably error-prone.

The main goal is attained if we succeed in giving students the feeling that assessments further their learning. This is achieved through formative assessment (lat. ‹formare›: to form, create).

This is closely connected with the concepts of self-regulation and metacognition, i. e. monitoring one’s own learning behavior, and to control, assess, regulate and direct it. Formative assessments serve self-regulation in a broader sense: feedback, self-regulation, regulation through others or with their help (co-regulation), regulation through the selection of appropriate learning assignments, learning contexts and learning technologies. Formative assessment goes hand in hand with the regulation of cognitions, emotions, motivation and attitude, and improves self- regulating, metacognitive and learning-strategic abilities.

5. Forms of assessment

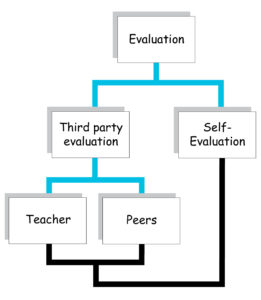

Among the everyday experiences in school is the experience that a person is not only judged by others but also evaluated by him/herself. The school is perhaps the place where one experiences the most and the greatest variety of assessments. The interaction of the various forms (see graphic below) is of central importance if the intention is to promote the sense of maturity, if individuality is appreciated, and learning is systematized and intensified.

In the future, both forms of evaluation, assessment by fellow students (peer-assessment, peer feedback) and self-assessment will take on a more prominent role in the schools.

This is connected with a less authority- accentuated approach and with more open instructional forms, allowing children and adolescents to study increasingly independently as well as collaboratively in groups, including mixed-age groups. In self-paced learning it is necessary to consider the assessments more explicitly and under one’s own direction, and in all phases of the learning process (Schmid, 2014, page 313): 1. Orientation, goal setting (assessment of expectations, assessment of the significance and the teaching content), 2. planning and preparation for learning (assessment of previous learning experiences, evaluation of potential learning pathways), 3. implementation of the planned learning steps and learning activities (assessment of the learning strategies, evaluation of the motivation) and 4. assessment of learning success, review and outlook (self-evaluation, assessment of learning achievements).

6. Assessment standards and benchmarks

Judging involves parameters and benchmarks:

- a) previous knowledge and competences

- b) the comprehensive understanding of the facts, the exemplary, ideal application of a skill or

- c) the achievements of others.

There are different situations which need to be brought into focus:

- Individual reference standards:

Comparison with one’s earlier achievements. The reference standard is intra-individual and refers to one’s personal learning gains and progress.

- Objective reference standard:

Related to competences and competence levels. The standard is related to criteria, learning objectives, and is competence-oriented, curricular, curriculum-based and absolute. The learning level is compared with a defined competence and classified as, for example, the six levels of language proficiency (A1 to C2) of the Common European Reference Framework (GER).

- Social reference standard:

Comparison with the achievements of others. In this highly competitive way of assessment, the reference standard is inter-individual, involving usually a class or a larger learning group. The decisive factor for assessment is the ranking position.

The evaluation based on personal comparisons is a very delicate, ethically questionable business with a potential for demotivation that is difficult to overestimate.

7. Utilize and encourage self-assessment

Self-evaluation is considered the centerpiece of self-regulated, autodidactic learning. It denotes an important area of metacognitive abilities. Self-assessments often take place automatically and self-evaluation skills are mostly acquired incidentally, unconsciously and implicitly, without attentional direction. Self-evaluation stems from individualistic educational concepts and, like many other compound words with „self“ – e. g., self-responsibility and self-reflection – and appears very modern. It also expresses enhanced social modes of behavior in the joint negotiation concerning education and school and is consistent with didactic „evergreens“ such as learning diaries, portfolios, weekly lesson plans and independent work. Self-evaluation can have many pitfalls, in spite of all positive connotations, and may be prone to ambiguities, contradictions, overload, idling, inefficiency, fault-finding or even repression. In cases of substandard performance in school, for instance, self-evaluation can easily take on forms of social declassing, self-condemnation and self-humiliation.

Self-assessment is important for the assumption of responsibility, self-control, independence from others, and for the development of autonomy.

The abilities for self-assessment are reflected in very different ways. Even university students manifest difficulties to accurately assess if they correctly understood something, or if they possess the appropriate learning prerequisites. Although self-evaluation must be purposely promoted, there is no corresponding curriculum. Until now, there exists only a relatively small empirical basis for successful techniques for self-assessment in the schools.

8. Criteria for orientation as a central principle

Criteria are essential for self-assessments: “in criteria-oriented self-assessments, learners obtain information about their own performances or advances. They correlate this information with clearly defined criteria, goals or standards and orient their future learning on the insights thus obtained” (according to Andrade & Valtcheva, 2009, page 12). Checklists with criteria for different proficiency levels (so-called scoring rubrics) can be very helpful for learning control, although not all checklist grids deserve their name. The criteria must be clearly described and in detail, with well-identifiable performance levels. Without the stated performance levels, they are considered mere rating lists or (“rating scales”). Only checklists in the proper sense with unambiguous criteria and elaborately defined educational levels are able to generate motivation and support goal-directed learning, as well as self-assessments and feedback by instructors and classmates.

It is certainly an advantage if the evaluation criteria are developed jointly with the students and later individually adapted. Superficial, over-generalized, unclear or misleading rating scales have a counterproductive effect.

The practice of self-assessment is demanding, independently of the utilization of criteria. The anticipated criteria must first be explicitly explained and common expectations should be clearly defined, if possible. The next practical steps must be well-planned. Even mere self-corrections may represent a great challenge for students. Certainly the less advanced students should be carefully introduced to the practice of self-assessment, and they must be helped particularly in utilizing self-assessment successfully for learning purposes. It therefore should not only occur at the end of a learning sequence, but also in the course of a learning process and at the beginning of a new learning sequence. It would not be advisable to utilize self-assessments for grading purposes. Certifying and issuing grades in report cards is entirely the responsibility of the teacher.

9. Portfolios for increased desire to learn

Portfolios have become very popular in the last few years. They offer a multitude of possibilities for self-assessment practice and the ability to systematically reflect ways, experiences, successes and strategies. In short, portfolios represent “kind of a systematic way to collect and document examples of personal achievement, learning processes, and of one’s own learning style” (Paris & Ayres 1994, page 167). Basically, portfolios can be used to great advantage for the assessment of learning successes (assessment of learning) as well as for the improvement of learning (assessment for learning), but not for both at the same time. Presentation portfolios (show and tell portfolios) are of more limited use. (Although they offer a practice field for differentiated summative assessments, they are not convincing as a substitute for more objective and more easily evaluated procedures (tests and learning controls). If the best efforts are not the primary aim of this exercise, but the development and learning in the course of time (portfolio of development, processes and body of work), it opens up a broad field for formative assessments without limits for didactic potential.Through systematic use of portfolios in classroom instruction in a climate of confidence and trust, they can become an instrument of communication and promotion. However, it is very likely that in practice by no means all hopes ascribed to portfolios may be fulfilled (Allemann-Ghionda, 2002; Lissmann, 2010). There is a lack of meaningful impact studies in terms of the portfolio’s utility for learning progress assessments, dealing with learning difficulties, and the promotion of learning strategies. However, the European language portfolio has established itself. (ESP; Giudici & Bühlmann, 2014).

10. Skill evaluation and certification (performance assessment)

“Car driving skills” cannot be evaluated by means of theoretical knowledge about driving in the city, but with a test drive through the city. Manufacturing products, performances, exhibits, assessing water quality…: everyday, practice-oriented and application-oriented tasks are in demand if relevant competences are the focus of attention.

Abilities, skills and competences, respectively, should be assessed in the applicable form as demanded outside of the school, wherever possible. “Authentic” evaluation also presupposes the contexts of the probation situation.

As a possible example for HLT, the students are tasked with documenting on a poster three examples of life together of different languages and cultures from their environment (grades 4-6 ), and respectively a scenic portrayal of three conflict situations and corresponding possible resolutions (grades 6-9). The results of this assignment are subsequently discussed and assessed in light of certain previously clearly declared criteria.

11. Minimize unintended side-effects

The learning objectives and competence requirements of school curricula must not be adapted to the learning checks and tests, but rather to the review procedures according to established curricula. The competence evaluations must reflect abilities and skills, as needed in life, understanding, transfer and all that which is central to classroom education. Then, they can have a positive effect on classroom education and learning, but they should be related to the core materials taught and learned. Basically, any evaluation procedure (assessment) should match the instructional goals (curriculum) and the teaching activities (instruction) and harmonize with the “alignment”.

This insight is often lost in the assessment that the performance of the students depends to a great extent on the cultural and economic circumstances, the social milieu, the school, the teacher, the schoolmates and other actors. An individual’s performance cannot be isolated from the determinants of his/her environment. This is particularly true for some of the HLT students who often only have limited chances, due to their migrant background, the educational background of their parents and their “foreign language”.

In many places, the assessment of learning success (“assessment of learning”) threatens to suffocate the promotion-oriented assessment (“assessment for learning”). In general, do all the students even have sufficient time for productive learning? Do they have the opportunity to show something that they really know, or are they constantly embarrassed with text exercises, when it is patently clear to them that they are not able to solve them at all? It is preferable to have learning controls which stimulate the interest of the learners and inspire new learning.

What needs to be certified and graded is essentially that what individual children or adolescents really know, that is to say the competences they have at their disposal over a longer period of time. Valuable additions to such “status diagnosis” is information about forthcoming development steps and the next learning goals.

Central to this is the long-term development of competences. In terms of HLT, it certainly involves primarily competences in the areas of a) mastery of the first language, b) acquisition of knowledge about their culture of origin and c) acquisition of competences concerning the orientation in the multilingual-multicultural situation of the host country (see also chapters 1 and 2).

A confusing jungle of mini-competences should be avoided. The focus on learning progress, as well as the learning assessments based on everyday-related assignments that enable helpful feedback for continuing education, are part of an assessment culture which complements the current learning culture and supports learning efforts. Ultimately, this includes learner participation in the developing process of learning controls, the critical evaluation and consideration of the learning conditions in terms of performance assessment, as well as the avoidance of any kind of stereotyping of the learners. A smart dilemma-management is required to avoid the possibility that the review process might turn into an easy testable narrowing of the curriculum. It must not negatively affect the students‘ feeling of self-worth and lead to a situation where individual qualities are seen, recognized and appreciated far too little.

Bibliography

Allal, Linda (2010): Assessment and the Regulation of Learning. In: Penelope Peterson; Eva Baker; Barry McGraw (Eds.): International Encyclopedia of Education. Vol. 3. Oxford: Elsevier, p. 348–352.

Allemann-Ghionda, Christina (2002): Von der Rute zum Portfolio – ein internationaler Vergleich. In: Heinz Rhyn (eds.): Beurteilung macht Schule. Leistungsbeurteilung von Kindern, Lehrpersonen und Schule. Bern: Haupt, p. 121–141.

Andrade, Heidi; Anna Valtcheva (2009): Promoting Learning and Achievement through Self-assess- ment. Theory Into Practice, 48,12–19.

Bildungsdirektion des Kantons Zürich (2013): Beurteilung und Schullaufbahnentscheide. Über das Fördern, Notengeben und Zuteilen. Zürich: Lehrmittelverlag des Kantons Zürich (downloadbare Broschüre).

Giudici, Anja; Regina Bühlmann (2014): Unterricht in heimatlicher Sprache und Kultur (HSK). Eine Auswahl guter Praxis in der Schweiz. Bern: EDK, Reihe “Studien und Berichte”. Link: http:// edudoc.ch/record/112080/files/StuB36A.pdf

Lissmann, Urban (2010): Leistungsbeurteilung ges- tern, heute, morgen. In: Günter L. Huber (eds.): Enzyklopädie Erziehungswissenschaft Online. Weinheim: Juventa, p. 2–41.

Nüesch Birri, Helene; Monika Bodenmann; Thomas Birri (2008): Fördern und fordern. Schülerinnen- und Schülerbeurteilung in der Volksschule. St. Gallen: Kantonaler Lehrmittelverlag. Link: edudoc.ch/record/32505/files/foerdernfordern.pdf

Paris, Scott G.; Linda R. Ayres (1994): Becoming Reflective Students and Teachers With Portfolios and Authentic Assessment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Schmid, Christoph (2011): Beurteilen. In: Hans Ber- ner; Barbara Zumsteg (eds.): Didaktisch handeln und denken 2. Zürich: Verlag Pestalozzianum, p. 235–266.

Schmid, Christoph (2014): Abschied von der Schwach- begabtenpädagogik. Handlungsmöglichkeiten im Bereich Bewältigung von Aufgaben und Anforde- rungen. In: Reto Luder; André Kunz; Cornelia Müller Bösch (eds.): Inklusive Pädagogik und Di- daktik. Zürich: Publikationsstelle der Pädagogi- schen Hochschule Zürich, p. 303–331.