Ingrid Gogolin

Preliminary remarks

The contributions to this handbook comprise arguments and examples for good heritage language education in many places and in various ways. On the one hand, they present framework conditions for good teaching, such as its localization within the educational system, the material equipment or the qualifications of the teachers. On the other hand, they concern the contents and process characteristics of classroom instruction,e. g.the principles of good educational design. If the good ideas presented in this handbook could be realized in all of these areas, the result would most likely turn out to be optimal heritage language education:

It would consist of an educational model that would assume its natural place within the educational system and that would contribute to universally-recognized educational goals. The acquired competences in these classes would have commonly-accepted educational value. The instructors would be optimally trained and have obtained further qualifications. They would enjoy formal equality with regular classroom instructors – with the same rights and obligations. Since heritage language education in the sense of this handbook only exists in the context of linguistically and culturally heterogeneous immigration societies, the goals of this kind of education and the practice of its teachers are oriented towards leading the learners to acquire those language skills which they need for a self-determined and responsible good life in their linguistically complex, heterogeneous and fast-changing environment. Heritage language education here joins the ranks of language instruction that is offered within an educational system – it is a more genuine and equitable kind of instruction, but also committed to pursue the same general educational objective. Moreover, it will be “well done” according to the principles described by Andreas and Tuyet Helmke in chapter 3 of this handbook.

In the following, I would like to illustrate some aspects of my vision of optimal heritage language education.

1. Optimal HLT promotes the ability for multilingualism

The questions about the function, importance and the shape of the optimal heritage language education can only be answered within an expanded scope of deliberations about social, economic, technical and cultural challenges which the school and extracurricular educational opportunities in the 21st century encounter. Ultimately, it is part of the key tasks of education (not only of school education), to ensure that children and adolescents have access to acquire the skills which they need in order to lead self-determined and responsible lives under the prevailing conditions of the foreseeable future. Globalization, international mobility and migration are significant challenges in the present as well as the foreseeable future, challenges which the educational systems have to meet. These developments cannot be reversed – on the contrary: it is to be expected that they continue to strengthen. As a result of these developments, there will be growing social and economic, linguistic and cultural homogeneity in people‘s daily environment – almost everywhere in the world. Among the skills that the educational systems of the 21st century have to facilitate in order to offer understanding and effective participation under these conditions, are those that fall under “global communication” (Griffin et al. 2012). This could be rendered as follows: the competence of being able to conduct oneself appropriately in the realm of linguistic diversity, as well as in linguistic uncertainty – in short: the ability for multilingualism.

The advantage of multilingualism consists of having at one’s command more than one language to a greater or lesser extent. At the same time, however, it means that a person is able to communicate in situations of language differences. The benefits of multilingualism thus comprise linguistic sensibility and flexibility and the competence to find means to communicate even if one does not speak the language(s) at all or only rudimentarily.

It is foreseeable that in the future, bilingualism increasingly determines everyday use of language. This applies in particular to urban regions. There is little empirical knowledge about the linguistic composition of the populations in European countries, as there is negligible reliable data about it. Unlike in certain “classical” immigration countries (e.g., USA, Canada or Australia), corresponding language statistics are not being collected in Europe. Single investigations show, however, that the intermingling of different languages in the large European cities is barely distinguishable from what is normally encountered in the classical immigration countries (Gogolin 2010). There can easily be several hundred languages in use by people who live in a large city.

Since it is therefore likely to encounter such a variety and diversity of languages anytime and anywhere, the ability for multilingualism also requires a relaxed and serene relationship relative to this linguistic situation. Multilingualism is our present and our future, and the more we accept it (or better: embrace it), the easier it will be for us to cope with it.

The competence for multilingualism is what schools and other educational institutions must endeavor to offer the young people who are entrusted to their care, so as to enable them to master the linguistic challenges of the 21st century. This challenge is also faced by educational entities that offer language learning opportunities outside of the official school system. Moreover, it pertains to any language instruction: the one of the general school and classroom language, as well as foreign language teaching and native language education.

Optimal heritage language education contributes to the students‘ ability to acquire the competence for multilingualism.

2. Multilingualism as a resource

Children and adolescents who have been actively living in two or more languages daily from an early age on have a good basis for developing multilingualism. Their growing up in two or more languages is an excellent training ground for further language acquisition. Children who grow up bilingually or multilingually have a considerable advantage in developing language awareness over children who are reared monolingually. For instance, they are able to distinguish at an earlier age than monolingual children between the form in which something is said and the content of an uttering. This is a particular intellectual achievement, which is supported by growing up in two or more languages. Furthermore, it trains cognitive abilities to which knowledge about a language and its functionality belongs as much as a sensibility for functions and effects of different modes of expression and the ability to select an appropriate expressive possibility, if more than one is available. Such competences are called meta-linguistic abilities.

Scientific studies have shown that children who grow up bilingually or multilingually have these advantages when they enter school. Existing studies have primarily centered on children between the age of four and six or seven (Bialystok and Poarch 2014). It is particularly significant for learning in school as it enhances the possibilities of positive transfer – that is the transfer of basic knowledge that was acquired in one language into another language. A child does not have to learn again for every new language that something in the past is described differently from a future occurrence. Only the respective other surface needs be learned which is expressed in the past and present in the different languages.

Growing up and living multilingually has advantages for the mental development of children and is a good prerequisite for other learning – not just learning languages. Any language instruction should therefore strive to take advantage of these good preconditions and contribute to their further development.

It is by no means certain that children develop these good prerequisites for language learning and learning in general beyond their educational career. They would need more encouragement to actively take advantage of these abilities in and outside of school, and they would need systematic support in the development of these competencies. This requires a resource-oriented consideration of their acquired bilingual or multilingual competencies and skills. That these skills and competences are not “perfect” is to be expected, particularly in the context of heritage language education. The students‘ acquired abilities are shaped in very different ways by their living environment and affected by the conditions under which they were acquired. This heterogeneity is vividly presented in various chapters of this handbook and it cannot be denied that it represents an obstacle for teaching. However, it is the foundation upon which continued learning and linguistic development must build.

In an optimal heritage language education environment, the students will not be regarded in light of their shortcomings,i. e.what they don’t know, or do poorly. Rather, particular attention will be paid to already existing competences and experiences. The design of learning opportunities will ensure a connection with learners‘ existing language abilities (not just native language skills) and competences, and this connection thus opens a pathway to their next learning step. This tenet, which aligns with Lew Wygotski’s findings in developmental psychology (Wygotski 1964), allows the students to build an increasingly robust foundation for their continued learning. Moreover, the appreciation of their skills and knowledge offers them a possibility to gain experience as competent learners – which is an especially important precondition for learning to succeed.

In optimal heritage language instruction, students‘ acquired linguistic experiences and competences are utilized as a resource for continued learning, and it is ensured that students gain experience as competent learners.

The meta-language abilities acquired in daily life belong to the special resources of children or adolescents who live in two or more languages. These must be further developed as much as possible through skillful guidance in the classroom so that they will not stagnate or waste away. It is a matter of progressively learning how to strategically apply these competences – in terms of language acquisition as well as for practice in daily life. Support for these competences occurs in that meta-linguistic practice is explicitly included in daily language practice. The main purpose is to encourage students systematically to compare the languages and varieties in which they live. This can happen on all kinds of language levels: on the level of pronunciation,e. g.the relationship between phonetic symbols and written characters (to support orthographic learning), on the level of the grammatical structure of language (to support morphosyntactic development), on the level of resonance of words and expressions (to support pragmatic development and methaphoric abilities) or on the para-linguistic level,i. e.mimicry and body language (since, here too, the meanings are by no means universal, but rather tied to linguistic-cultural traditions and customs). The systematic inclusion of comparative language learning in native language classrooms is a specific part of cognitive activation, which is at the core of learning effectiveness (see Helmke and Helmke in this volume, chapter 3A, 2.2).

In optimal heritage language education, comparative language learning is systematically implemented as a means of cognitive activation. The basis for this is the students‘ own language competence and knowledge, acquired in daily life experience.

3. Heritage language education as an element of continuous language learning

Heritage language education that contributes to the students‘ ability to acquire the requisite language competences for the 21st century is without a doubt an official and publicly recognized part of the educational system, into which it is integrated. This integration can certainly occur in various forms. In light of the wide range of languages which can potentially be represented in a school through their students, it will not always be possible to respond to the demand with a single organizational form. Instead, it is necessary to find creative possibilities for their integration and to provide them with legitimacy.

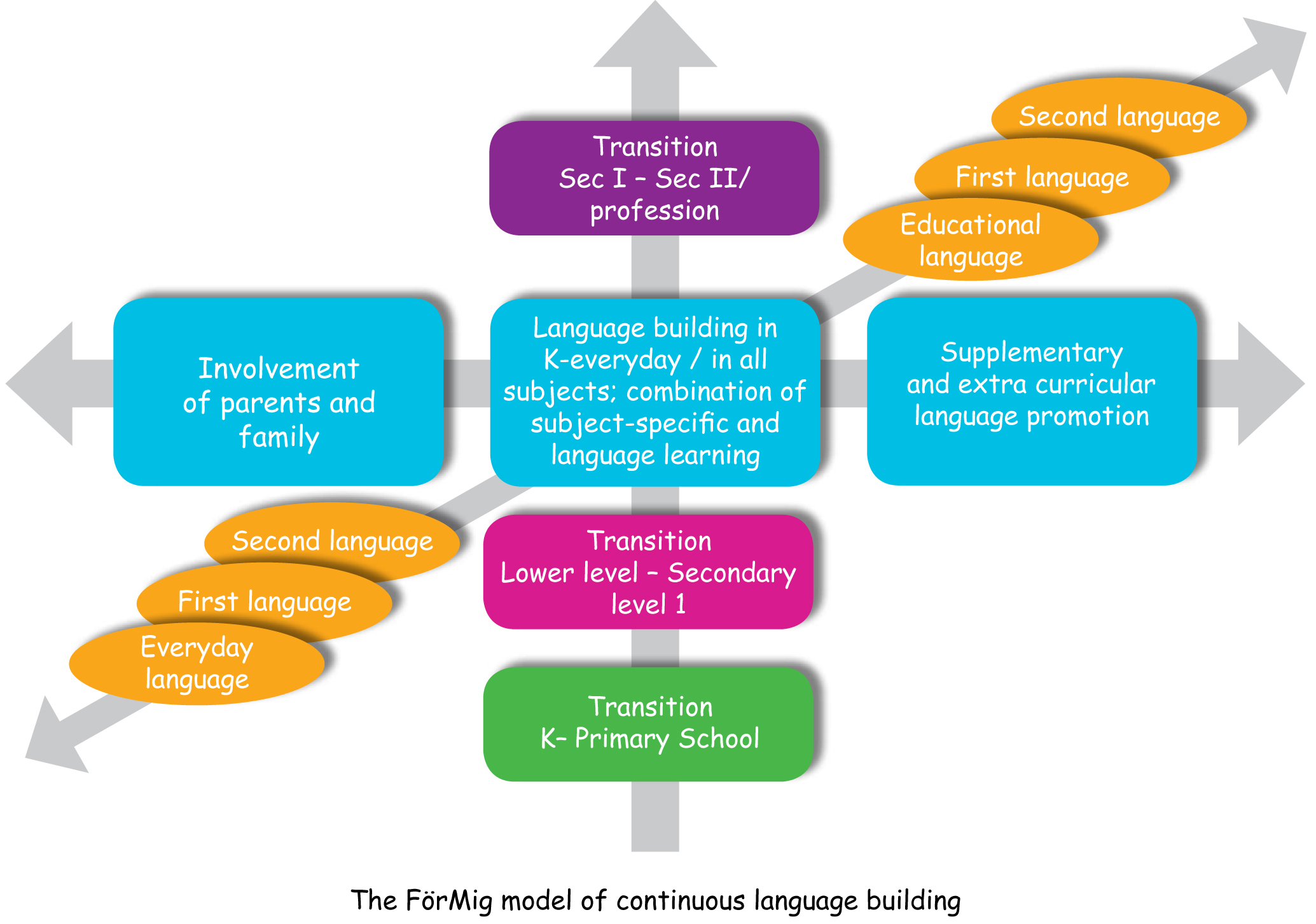

In the context of the model program “Furthering of children and adolescents with a migration background” (called FörMig in German), a framework model was developed which may show the way to such an integration: the model of continuous language learning (Gogolin et al. 2011a). The model was developed with the intention of demonstrating the way to a “new culture of language learning” that would enable a prudent response to the challenges of linguistic and cultural diversity.

The term language building was chosen to demonstrate that it is not just a matter of taking sporadic measures from time to time, for instance, a single classroom project per school year. What really matters is to create a lesson plan that is altogether conducive for language building and that a language -attentive and language – furthering climate be clearly discernible in the entire school building. This responds to the insight that language processing is a fundamental element of just about any type of learning process. Learning topics are presented predominantly with language terms – regardless of the type of teaching. The acquisition of knowledge is primarily processed through language. Finally, the review and assessment of the acquisition‘s success is predominantly based on language. The model of continuous language building draws attention to this dimension of any learning process and raises a claim that instruction must indeed provide what is expected from the learners in terms of language competence and knowledge.

The flow concept refers to three dimensions of the model, which are illustrated in the graphic:

- The educational biography dimension.

This suggests that the demands on language competence and knowledge are changing throughout the entire educational path. The linguistic repertoire required in order to penetrate a surrealistic poem by Orhan Veli, for example, cannot be reasonably taught in elementary language instruction – it is rather to be addressed when the learners are dealing with the subject matter.

- The cooperative dimension.

This refers to the fact that it is not the task of “a” lesson to provide the requisite language competence and knowledge that children and adolescents need to accomplish the educational requirements for their entire educational biography. Rather, every class contributes to it in its own special, subject matter -appropriate way. The higher the unity between the participants about the ways and goals of and their corresponding share on language education, the higher is the chance that a successful acquisition process can be reached. This is justified by the postulate of cooperation, which holds that when all concerned contribute collaboratively to language learning, an efficient educational process can be established.

- The language development dimension.

This alludes to the fact that it is the task of teaching to build bridges for the learners between their experiences from everyday language practice in their environment and the language challenges which have to be mastered for a successful educational process. Daily life language practice occurs to a great extent orally, often in dialectal or social variants of a language. These are what instructors may expect in terms of educational prerequisites for their classes. Language-specific requirements on the other hand follow mostly the principles of written language usage. However, teaching the art of reading and writing, the access to the world of writing is the explicit task of the educational system. This is what is referenced as continuous language education in this dimension: to build bridges between the acquired language experiences outside the educational system and those requirements by the system itself – from everyday language to the educational language; from everyday multilingualism to multilingual competence in the education language (see also the article by Neugebauer and Nodari in this volume).

There is no recipe book for implementing the continuous language education model into practice. On the contrary, it is necessary to make an adjustment to the terms under which educational institutions operate. In terms of heritage language education, it is obvious that a school community where students attend just a few native languages, must operate in a different way than schools that are frequented by students of twenty or thirty different native languages. Experiences with educational offerings that respond to a given situation have been collected and documented in the context of the FörMig model program – they can probably not be “cooked up” or replicated, but they do offer helpful tips (e.g. see Gogolin et al. 2011b or the varied suggestions on the website www. foermig.uni-hamburg.de).

4. Examples for optimal heritage language education

To conclude my remarks, I should like to present two examples in which the patterns of an optimal native language education in terms of the described visions can be identified. Both examples derive from real practice. Moreover, they are at the same time tried and tested and utopian.

Literacy according to the zipper principle

Let’s imagine an optimal heritage language education classroom in an elementary school. This instruction is part of the everyday school setting – it takes place within the regular curriculum, and the teachers have the opportunity to consult with each other and work together in creating the lesson units for the next few weeks in a cooperative fashion. The instructional goal is the introduction of the first letters. The purpose of the cooperation between the teachers is to afford the students transfer strategies in learning how to write. Let’s further imagine that in this school community there are children with different native languages, which are transcribed in different ways.

It is recommended in this constellation to proceed along the zipper principle of alphabetization, as described by Hans Reich (see article referenced in this volume): in the common school language (for the purposes of our example: German) the connection between each individual phonetic symbol and letter to be learned is first introduced; the known symbols in the various heritage languages will be reviewed and related with the written forms appropriate for the respective language.

Following this principle of interlocking learning opportunities in German and in the native languages, instruction will be shaped throughout the entire school time. This can be expressed, for instance, in that the children acquire a learning-relevant basic vocabulary, offered comparatively in both languages, that they encounter literary genres by comparison, or that they learn the function of syntactical phenomena as different building principles of the respective language in a comparative fashion. This way a specific learning space is opened for each respective language, but the cognitive activation in the classroom occurs along a common principle, which helps the children expand purposeful strategies of language acquisition and use of linguistic means.

Heritage language education as a door opener for consistent language education

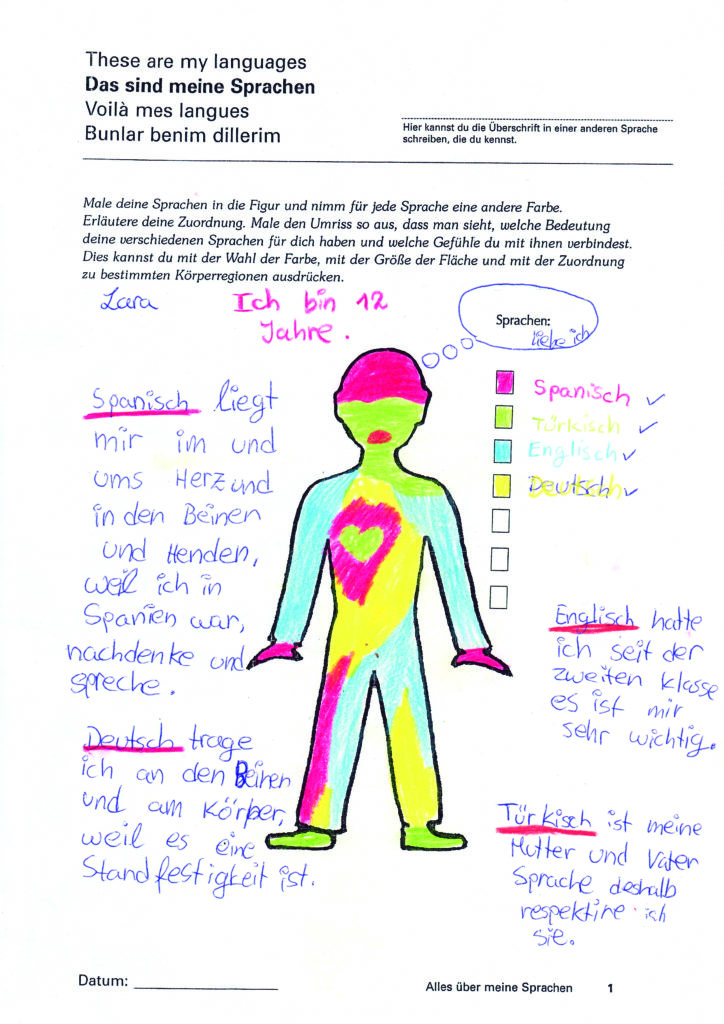

The children and adolescents who attend native language education have the privilege of living in two or more languages. It should be a goal of heritage language education to share the privilege with the community of the teachers and learners. This can happen if common activities are initiated which in turn contribute to open people’s eyes to discover multilingualism and its advantages, as described in the following example. A high school in Saxony – a German federal state with a relatively low immigration rate – participated in the FörMig model program. This particular school offered native language education in Russian; but the student body make-up includes students with other native languages as well. The school proudly presents its “multilingual profile”. To that end, it conducted a ritualized activity at the beginning of each school year to collect the language experiences of the students who enter into 5th grade (that is the first year of high school). The German teachers and those of heritage language education work together in this effort. The survey includes the “language portrait” designed by Ursula Neuman, comprising the outlines of a girl or a boy, into which the children write in color their language make-up,i. e.the languages which they “have” (Gogolin and Neumann 1991); see picture below.

For one, these portraits serve our Saxon model school as an update of the “language survey assessment”, which the school conducts regularly for itself. For another, they serve at the same time as a basis for the thematization of the linguistic self-image and the promotion of language awareness with the children in class. For instance, this can occur by joint, collaborative work on language portfolios between heritage language education and German language and foreign language instruction, which document the development of multilingualism of each individual child (Department of Education, Canton of Zürich 2010).

It is this kind of bridge-building between the language environment of children and adolescents, their multilingual development, furthered by classroom education, and the contributions to a “new culture of language education”, that facilitate the optimizing of heritage language education in the multilingual living environment.

Bibliography

Bialystok, Ellen; Gregory Poarch (2014): Language Experience Changes Language and Cognitive Ability. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 17 (3), p. 433–446.

Bildungsdirektion des Kantons Zürich (eds.) (2010): Unterrichtsmaterialien und -ideen für die Arbeit mit dem Europäischen Sprachenportfolio. Unterstützungsmaterialien zur Einführung des Europäischen Sprachenportfolios ESP (Portfolino, ESP I, ESP II). Zürich.

Gogolin, Ingrid (2010): Stichwort. Mehrsprachigkeit. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 13 (4),

p. 529–547.

Gogolin, Ingrid; Ursula Neumann (1991): Sprache – Govor – Lingua – Language. Sprachliches Handeln in der Grundschule. Die Grundschulzeitschrift, 5 (43), p. 6–13.

Gogolin, Ingrid; Inci Dirim; Thorsten Klinger; Imke Lange; Drorit Lengyel; Ute Michel, et al. (2011a): Förderung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Migrationshintergrund (FörMig). Bilanz und Perspektiven eines Modellprogramms. Münster:

Gogolin, Ingrid; Imke Lange; Britta Hawighorst; Christiane Bainski; Andreas Heintze; Sabine Rutten; Wiebke Saalmann, (2011b): Durchgängige Sprachbildung. Qualitätsmerkmale für den Unter- richt. Münster: Waxmann.

Griffin, Patrick; Barry McGaw; Esther Care (eds.) (2012): Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills. Amsterdam: Springer.

Wygotski, Lew Semjonowitsch (1964): Denken und Sprechen. (Übersetzung der russischen Original- ausgabe von 1934 durch Gerhard Sewekow.) Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.